Brazil political risk for infra investors

Brazil’s political risk is declining after a decades of tumultuous events. The political crises involving ex-President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, Odebrecht, Petrobras and Operation Carwash remain painful reminders to investors worldwide of unmeasured political economic risks.

A slate of reforms is underway to clean up its act, but will these reforms engender investor confidence and transparency after decades of political tumult?

Brazil’s need for infrastructure investments over the next 20 years is estimated at $1.3 trillion across all market segments from schools through to roads, hospitals and logistics. The size of its infrastructure needs can only be met by inspiring investor confidence that these reforms provide a stable country for growth with genuine transparency.

This is important as Brazil’s ability to pile up more debt for growth is constrained by the limits of its fiscal policy. Debt levels are troublesome and GDP is anemic coming out a recession (Chart 1).

The challenge remains for how investors measure whether or not these reforms are improving Brazil as a place for investment for infrastructure projects – all the more important as traditional risk measures are inadequate to track real progress. Rather, it requires an innovative approach to measure whether these reforms are improving political risks for infrastructure investments in quantifiable terms.

What Brazil is actually doing

Brazil is undertaking real efforts to clean its act up. It is currently attempting to reorganize a byzantine structure by reducing the number ministries and political interference in regulatory agencies´ work, reform pension fund regulations.

It is doing this by instituting the Economic Freedom Law which will reduce bureaucracy for SMEs and reforming social security which will save $250 billion over the next few years, as well as introducing the Infrastructure Debenture Law which impacts freedom from income tax, and initiates tax reform. Finally, the Government will dispense with regulating profits from infrastructure investments.

The role of BNDES, the state-run infrastructure fund, is being reformed as well. In the past, investors depended heavily on BNDES guarantees to invest in Brazil. The new idea is that more attractive regulatory and macro economic conditions will take over as dominant motives for investors and BNDES will assume the role of a service agency to help structure projects.

The Federal Government aims to raise $54.1 billion in infra investments by 2022 – 57.5% of the $94 billion that Brazil needs by that date, according to Global Infra Hub. The biggest share goes to roads with $35 billion, followed by $15.52 billion for 1,470km of railroad. Airport privatization account for $2.57 billion and $1 billion for ports.

Yet in early November (2019) Brazil suffered a setback in its first major auction of deepwater oil assets. The auction was intended to raise $25 billion for four deep-water assets. However, two received no bids and two went for lowest prices.

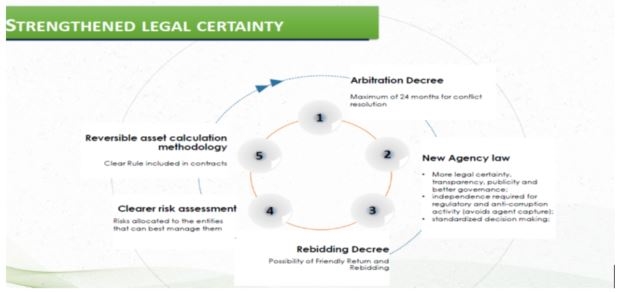

The federal government´s plan is not only to improve conditions, but to raise transparency about the real risk of investing in Brazilian infra. Under the heading of "strengthening legal certainty", which, in effect, means reducing political and regulatory risk (Figure 1), the Government pledges to pursue "clearer risk assessment".

The bottom line is that uncertainty costs money. Investors demand a premium in basis points to compensate for this. Brazil is still burdened by uncertainty over its political and regulatory environment – not to mention historic macro economic instability. In Q4 of 2015, Brazilian GDP growth dropped to -5.5% and for 2019 it is projected to reach 0.9%.

However, investors can hardly afford to ignore Brazil, the World´s ninth largest economy with a population of 209 million and a GDP of more than $3 trillion. The main states – Sao Paulo and Minas Gerais – themselves are significant economic powerhouses.

The State of Sao Paulo is LatAm´s second largest economy, next to Brazil itself, followed by Minas Gerais. Sao Paulo´s GDP growth has significantly outpaced that of Brazil as a whole by hundreds of basis points, projecting growth at 1.5% for 2019 (Brazil: 0.9%). By 2022 Sao Paulo projects to grow by 3.6% (Brazil: 3%).

Translating reforms into infra investment opportunity

Brazil needs to inspire investor confidence with measurable risk/return data. Traditional investment metrics will not demonstrate the impact of reforms and improved investment conditions. A new, more quantitative approach is needed.

Value for Risk (VfR) is a deep-dive data analytics method to measure 200+ actual political and regulatory risks as an indispensable element of value. VfR helps remove the lag between investor perceptions of a country and the updated regulatory reality of that country by quantifying the real risk in basis points. This allows investors more accurately to discount expected cash flows from a project.

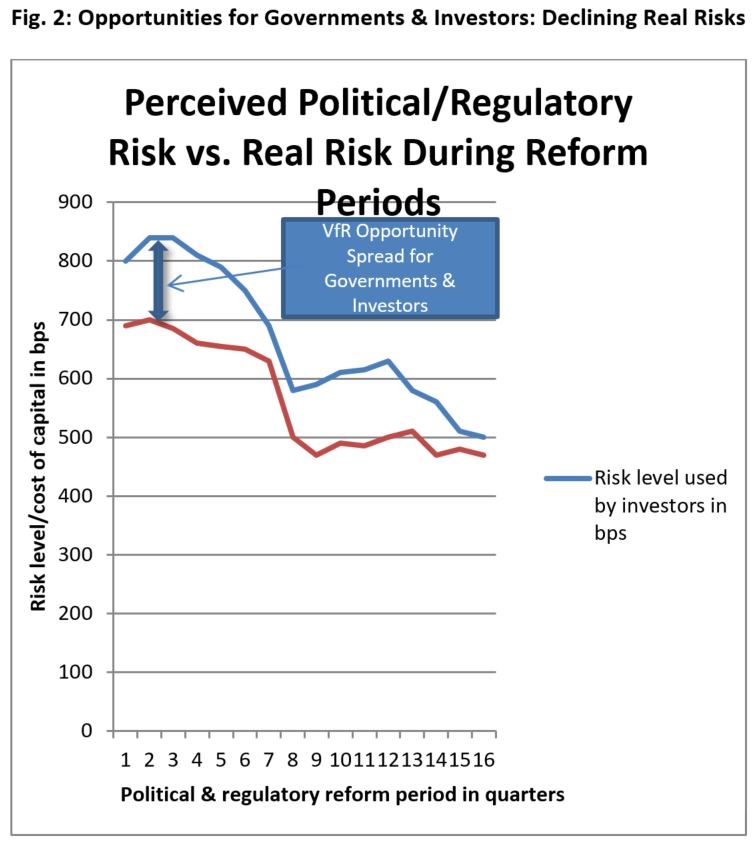

A typical VfR Opportunity Spread between real political and regulatory risk and perceived risk would look like this (Figure 2) over a four-year period in which reforms are being implemented.

Typically during a political and regulatory reform period, spreads between real risk as calculated in detail by VfR and risk measures used by investors range between 50 and 150 basis points. This can easily entail tens of millions of dollars in the net present value of a project´s cash flows. Expressed in basis points, the financial opportunities that investors are missing become more tangible.

These spreads diminish towards the end of a reform cycle, which often tends to last four years. The greatest discrepancy between real risk and perceived risk occurs in the first 1-2 years of the reform or regulatory change process. However, the spreads do not tend to decrease in a linear fashion. Once investors and rating agencies catch on to a country´s declining political and regulatory risk, they tend to make a fairly major adjustment of risk rates downwards (Figure 2). Even so, they are still behind the actual risk curve as reforms begin to take hold fully. Thus, in the case of countries involved in reforms impacting infrastructure, investors lose four years or more due to lagging and inaccurate risk assessments.

VfR generates an updated risk rate in basis points, in the form of a discount rate, as political and regulatory reforms are successfully implemented. This rate is specific to:

- country

- infrastructure sector – roads, rail, ports, etc.

- period

- project type – PPP, etc.

Investors can determine their specific total risk and each specific risk in basis points.

The main areas covered by VfR include:

- governance

- legal

- political processes

- ease of doing business

- judicial processes

- investor protection

- cultural and social facets

- efficiency of regulatory processes

- environmental

The VfR process is dynamic and adjusts to changes in any area as they occur, but is normally updated on a quarterly basis.

Previous articles published on IJGlobal by Mathew Garver & William Cox include:

Request a Demo

Interested in IJGlobal? Request a demo to discuss a trial with a member of our team. Talk to the team to explore the value of our asset and transaction databases, our market-leading news, league tables and much more.