News+: Caution, sharp U-turn ahead

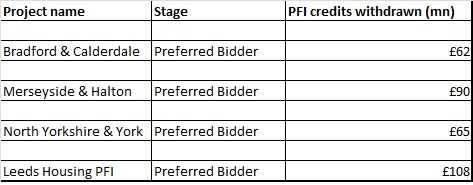

The UK Treasury shocked three UK local councils last week when it announced withdrawal of PFI credits that were committed to waste deals being procured by the three councils; Bradford & Calderdale, Merseyside & Halton and North Yorkshire & Yok. A few weeks prior to that, PFI credits were also snatched back from Leeds council which was running a contract to re-build housing at three locations within the council.

In its statement justifying the credit withdrawal from the aforementioned waste projects, the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) said that the government was already supporting 29 waste deals in the UK amounting to £3.6 billion (US$5.4bn). DEFRA added that, "...we now expect to have sufficient infrastructure in England to enable the UK to meet the EU target of reducing waste sent to landfill. Consequently the decision has been taken not to fund the remaining three projects."

Granting PFI credits to projects and then making a sudden u-turn on them is not a new pattern in the UK. The government administered PFI cuts in the waste and housing sector back in 2010 and in some instances even cancelled entire PFI procurement programmes - such as the Building Schools for Future programme. Since then PFI cuts have been more sporadic and inconsistent, but there are many examples where highly leveraged deals that were financed at steep margins managed to escape the axe. So surely three waste deals themselves cannot possibly topple the government's budget?

The latest PFI casualties (source - Infrastructure Journal):

DEFRA has said that their decision does not spell death for these projects, "...this does not necessarily mean the three projects will stop. That will be a decision for the Local Authorities concerned." But it will undoubtedly become quite difficult for these councils to pay their way through the 25-year concessions sans government support. The three local authorities are not exclusive to the EU landfill targets and if they do plan to continue with the procurement, they will possibly have to pay higher unitary charges due to the lack of government backing financially.

The other frustrating factor is that the four deals mentioned above are at advanced procurement stages and together the respective councils and their selected private sector partners have already spent a considerable amount on the bidding process. In addition the local councils had also cleared the long-drawn planning hurdle on some of these waste plants. All that might go down the drain, if the councils are ultimately unable to find financing for the projects.

DEFRA's justifications aside, there is a strong sense in the industry that the government has taken these recent steps to send out the message that deals they don't consider financially feasibly will not be allowed to proceed to financial close no matter what stage they are at.

High Margins

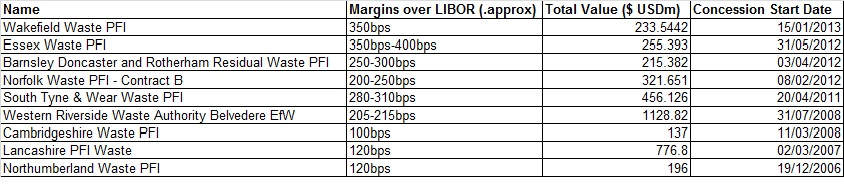

The reality is that bank financing costs are much higher today than those during the pre-crisis era (see: chart below) which is a reflection of the change in financing landscape brought about by the financial crisis and impending new regulations like Basel III, which restrict a bank's funding appetite. And funding costs are not likely to come down any time soon, besides there are still many waste deals that are in procurement at the moment where private financing will be required.

Pricing comparison on waste deals (source - Infrastructure Journal):

Sources close to the waste sector doubt that the projects which lost their PFI credits were hugely expensive compared to others which reached financial close in recent months. So while the government is subtly indicating that there are certain rules it would like the private sector to adhere to, it will have to actually make sure it isn't ultimately driving them away when making sudden moves like these.

Surprise withdrawal of PFI credits from projects or even dumping the private finance route on large deals, as the government did with the Crossrail project last week, doesn't only hurt the projects themselves, it also harms investor appetite in the long-term. The four private sector consortia bidding on Crossrail were left stunned as the government announced that it would fully publicly cover 100 per cent of the project costs, which is around £1 billion.

Developers, advisors and financiers who may have worked on a project for five-long years before it suddenly faces the red light, might become more wary of investing in future projects which will eventually affect the UK's ambitious infrastructure development plans.

Request a Demo

Interested in IJGlobal? Request a demo to discuss a trial with a member of our team. Talk to the team to explore the value of our asset and transaction databases, our market-leading news, league tables and much more.