Panama weighs up the alternatives

Early last week (August 2018) the governments of the US and Panama signed a memorandum of understanding to promote energy and infrastructure investments in the Central American country. A particular focus of the agreement is an attempt to catalyse private sector investments into upstream energy production, power generation, transmission and distribution, and energy use projects.

The Panamanian infrastructure sector is in need of a catalyst. It was hit hard by the sprawling ‘Lava Jato’ corruption scandal which consumed Brazilian engineering company Odebrecht, as it left a number of the country’s power projects in limbo. In 2016 the government banned Odebrecht from participating in future tenders in the country and terminated its contract for the $1 billion, 213.6MW Changuinola II (Chan II) hydropower plant in Bocas del Toro province. A new tender for Chan II is due to be launched this year (2018).

Odebrecht had been one of the most active developers across a number of sectors in Panama but was forced to admit to the US Department of Justice, as part of its corruption investigation, that it had paid bribes to public officials in Panama and various other Latin American countries. Its exit from the market was particularly painful for Panama’s power sector given the country’s uncertain energy supply.

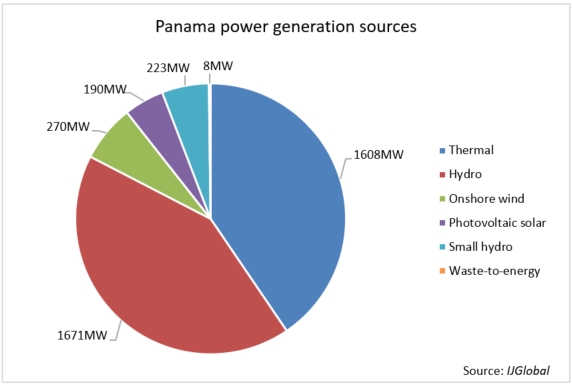

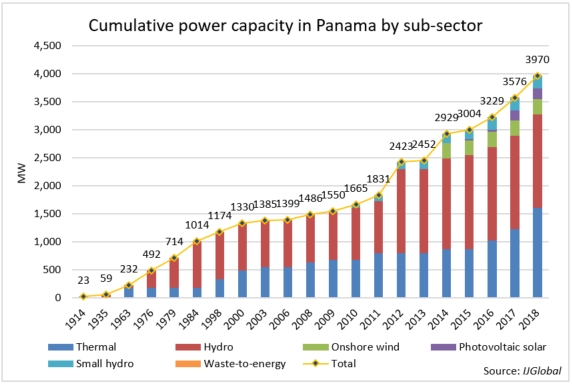

As shown by IJGlobal data, Panama has up until now been heavily reliant on hydropower for its energy needs. However, rising environmental and social concerns – and the delays to Chan II – have forced the government to look to other energy sources.

After just 27 months of construction – one of the shortest periods for such facilities in Latin America, according to POSCO Engineering & Construction – Panama’s 381MW Colon gas-fired power plant was officially inaugurated on 21 August (2018). The plant was developed as part of AES and Grupo Motta’s $995 million LNG-to-power project at the Caribbean port of Colon. The facility’s output will account for nearly a quarter of the country’s total energy production and will supply the Panama Canal, various industries and the equivalent of 150,000 households in Panama City.

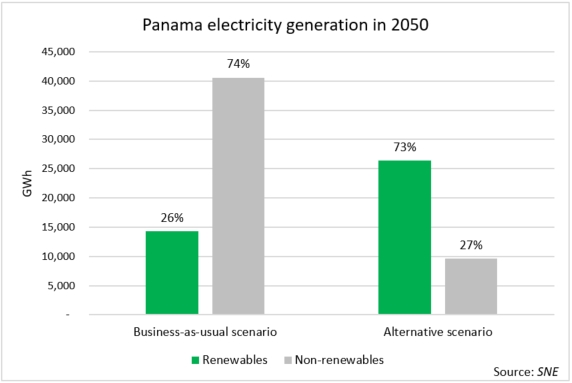

The development of LNG plants is part of the Central American country’s National Energy Plan 2015-2050 unveiled in March 2016. While new gas-fired plants are needed to plug a gap in baseload capacity, particularly given delays to the development of Chan II, the paper came with a promise to steer Panama away from conventional energy reliance, flaunting an impressive renewable energy target to be achieved mid-century.

It set out a business-as-usual scenario whereby supply would come from coal-fired and gas-fired generation, but also an alternative scenario in which over 70% of the energy mix would come from renewable energy sources – particularly solar and wind.

The Panamanian government has cited tax and other incentives for developers – such as government-backed PPAs – as ways to encourage the construction of new renewables projects. Still, renewable energy remains less attractive for investors in comparison with conventional energy, as the government deemed it less reliable at providing firm capacity at maximum operating conditions.

Progress has been limited, but some projects have progressed in recent years. In one recent deal, Vestas scooped a turbine order for the 66MW first phase of Toabré wind farm.

Panama’s wind resources are spread throughout the country, with wind speeds strongest along the Caribbean coast and at several wind passages on mountain ranges. Panama has 270MW of installed wind power capacity, located entirely in the municipality of Penonomé, in the province of Coclé. This capacity is spread over two projects – the Penonomé I and II wind farms. According to the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), provisional licences for 870MW have now been granted for future wind farms.

The solar sector has a lot of potential too, though Panama was slow to start promoting the technology. Solar development started in 2013, with limited applications in rural and industrial areas. According to data compiled by IJGlobal the country has around 190MW of solar generation installed, with provisional licences for a further 376MW.

Given several large transport projects in the pipeline, like the expansion of the Panama Canal, electricity is expected to grow. Panama’s state power transmission company Etesa forecasts energy demand to grow at an average rate of 6% until 2030. The 2016-2030 grid expansion plan proposed by Etesa foresees boosting the security of supply by a handful of backbone projects, namely:

- construction of the 317km, 500kV Panama Fourth Electric Transmission Line, which will have a capacity of 1,400MW

- the Colombia-Panama Interconnector, which consists of an underwater cable with a 300MW capacity from Colombia to Panama and 200MW in the other direction

Panama will hope that its new agreement with the US government will help it meet its ambitious targets for diversifying its energy mix and extending access to power.

Request a Demo

Interested in IJGlobal? Request a demo to discuss a trial with a member of our team. Talk to the team to explore the value of our asset and transaction databases, our market-leading news, league tables and much more.