Meeting future demand

While the market may be awash with gas now, demand for LNG is set to grow steadily over the next decade.

As countries around the world look to embrace clean-energy and turn their backs on coal, natural gas is being widely used as a bridge fuel to support the development of renewable energy.

Global demand for natural gas is expected to increase 2% a year between 2015 and 2030, with LNG demand expected to rise at twice that rate, according to a recent report from Royal Dutch Shell.

But with numerous LNG export facilities coming online around the globe in recent years, there is currently a glut of gas. This has made it more difficult to get the construction of new export terminals off the ground, with new long-term sales contracts difficult to negotiate at bankable rates. So, although lots of projects wait to move forward, research suggests we could face an LNG deficit by 2023.

An opportunity

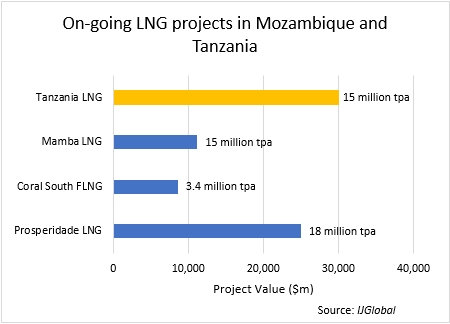

This creates a great opportunity for LNG projects that have been approved and are in development. The new East African LNG projects in Mozambique (Prosperidade, Mamba, Coral South) and Tanzania could all be coming on-stream at exactly the right time. These projects were launched after major gas discoveries were made offshore South East Africa in the years 2010 to 2014.

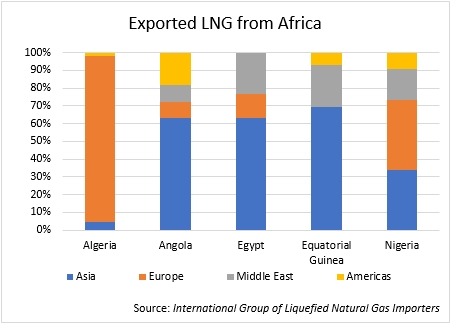

Although the existing facilities in North and West Africa export mainly to Europe (17.8 million tpa vs 9.7 million tpa for Asia, according to International Group of Liquefied Natural Gas Importers), Asian LNG markets could turn out to be paramount for the East African LNG exports. First LNG shipment from Mozambique is expected to be either in 2023 or 2024 with Tanzania to follow 4-5 years later.

Challenges

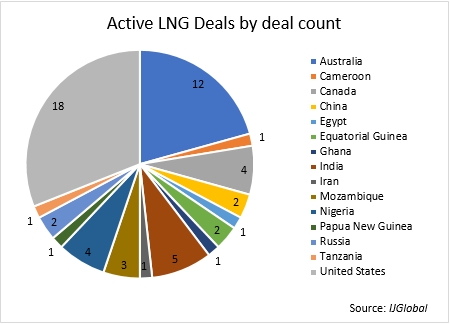

A string of new LNG developments in Australia, North America and Russia alongside existing ones in the Middle East, means timing is everything with the East Africa projects. If the offtake agreements get signed too early, the new projects could feed into an already oversupplied market. But if signed too late, the projects could miss the projected period of constrained supply and come on-stream at the same time as several other planned export projects around the world.

The East African projects will retain a geographical advantage even if they are delayed, as they benefit from being closer to India and Pakistan than the Australian LNG facilities and most of the growing gas production in the Middle East will be needed for domestic purposes to cover increased gas consumption.

But East African gas will need to be exported as LNG, due to the limited domestic markets and poor pipeline infrastructure, pushing up costs due to transport and complex technology (pumping gas extracted from below the ocean floor, freezing it to liquid form on a floating platform, and transferring it into tankers for export).

Costs have not proved to be much of a barrier to investors to date. China has set out plans to pour almost $7 billion into FLNG projects in Africa, while oil and gas majors like Statoil, Shell, ExxonMobil, Eni, Ophir Energy, Anadarko and others are also investing billions of dollars in the region.

If developers can get sales contracts signed at the right time, the east coast of Africa could soon become a hub for the LNG industry.

Request a Demo

Interested in IJGlobal? Request a demo to discuss a trial with a member of our team. Talk to the team to explore the value of our asset and transaction databases, our market-leading news, league tables and much more.