The rise of the green bond

Green bond issuers are no longer limited to development finance institutions. In recent months, ContourGlobal, TerraForm Power, Vestas, Transport for London (TfL) and National Australia Bank launched their first green bonds.

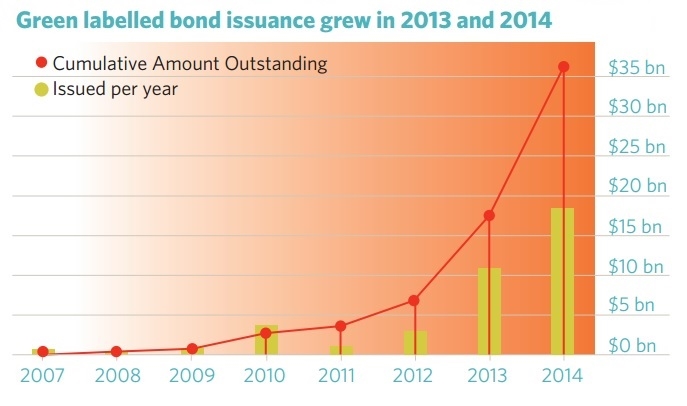

Issuers expect to benefit from a deepening pool of environmentally minded investors – many of whom are designating more capital to green bonds. Green bond volumes are indeed growing. In 2013 issuers launched $11 billion in green bonds, according to the Climate Bonds Initiative. In just the first half of 2014, $18 billion was issued.

But despite the spate of launches, little evidence suggests that green bonds are finding significant costs savings over traditional bonds.

Source: Climate Bonds Initiative

Advantages?

At best, green bonds have enjoyed a slight pricing advantage over traditional bonds.

The 2014 green bond for the North Island Hospitals PPP in British Columbia, for example, priced at about 165bp over the 2037 Government of Canada benchmark bond for a coupon of 4.39%. That spread was below traditional project bonds that closed that year for other Canadian PPPs. On its 2014 green bond issue for the Energía Eólica wind farms in Peru, ContourGlobal obtained pricing lower than comparable renewables project bonds.

But these green bonds may be exceptions today.

“Right now, green bonds yield about the same as regular bonds,” says Cathy DiSalvo, investment officer at the California State Teachers' Retirement System (CalSTRS) in Sacramento, California. “For now, at least.”

“Investors are not going to take a big price cut,” says Sean Kidney, founder and CEO of the Climate Bonds Initiative in London. “It has to be comparable pricing to other bonds.”

The narrow pricing differential has encouraged few renewables sponsors to pursue green bonds, or green bond certification. In 2013, MidAmerican Energy (which now goes by Berkshire Hathaway Energy), opted for a 144A/Reg S financing for Solar Star, a 579MW solar complex in California, without the green bond label. The $325 million follow-on bond priced earlier this year at 183bp over the 10-year US Treasury for an attractive coupon – 3.95%.

But issuers that are not perceived as pure-play green companies may stand to gain more from green bond issuances.

“What we need is clarity for companies that are not obviously green – like real estate companies on LEED certified buildings,” says Marshal Salant, global head of Citi’s alternative energy finance group in New York.

TfL, for instance, priced its first green bond in April 2015. The company was able to “unlock some sources of capital that were ring-fenced for environmental and socially responsible projects,” says Simon Kilonback, TfL’s director of group treasury in London.

The green bond concept

About eight years after the European Investment Bank issued the first bond that assigned proceeds for an environmental purpose, and about seven after the World Bank issued the first green bond, the concept still seems to be firming up.

No single authority determines what is, and isn’t, a green bond; and the Green Bond Principles – widely thought of as the ultimate guideline – outlines very broad criteria.

“Generally, my impression is that green bond is branding more than anything else,” says Mario Angastiniotis, a director at Standard & Poor’s in Toronto. “It’s a way of reaching new investors.”

Green bonds are not always labelled as such in documentation, and some – including a 2015 issue launched by TerraForm, SunEdison’s yieldco – lack certification.

It’s more of a concept, says Suzanne Buchta, global co-head of green bonds and market linked notes at Bank of America Merrill Lynch in New York. “Even if it doesn’t have the green bond label, but proceeds are clearly supporting environmental projects, that would still be a green bond.”

Some bonds have earned the label after pricing. The 2013 Solar Star issue, for instance, wasn’t marketed as a green bond. “We initially bought it because it was a good credit investment, but later realised that it qualified as a green bond,” says CalSTRS’ DiSalvo.

Stamp of approval

Certification, however, gives investors assurance that the proceeds are being used for environmentally responsible purposes, DiSalvo says. Investors have thus far included pension funds, endowment funds, insurance companies, banks and universities.

The cost for a Vigeo-certified green bond is typically less than half a percent of the cost of an issue, says Lindsay Smart, the company’s head of UK and US markets at Vigeo in London. Vigeo, the Climate Bonds Initiative and DNV GL are among the entities that offer certification services.

These entities take different approaches to certification. Vigeo prioritises environmental, social and governance responsibility, while the Climate Bonds Initiative weighs influence on climate change more heavily.

More issues to come

In the next wave of green bonds, yieldcos are expected to be among the active issuers.

Earlier in 2015, TerraForm launched an $800 million green bond to finance its acquisition of First Wind’s operational assets, and to refinance outstanding debt. In 2014 NRG Yield issued $500 million in green bonds to fund its acquisition of 947MW at the Alta wind complex in California.

Request a Demo

Interested in IJGlobal? Request a demo to discuss a trial with a member of our team. Talk to the team to explore the value of our asset and transaction databases, our market-leading news, league tables and much more.