Data Analysis: Renewables push gas aside in Germany

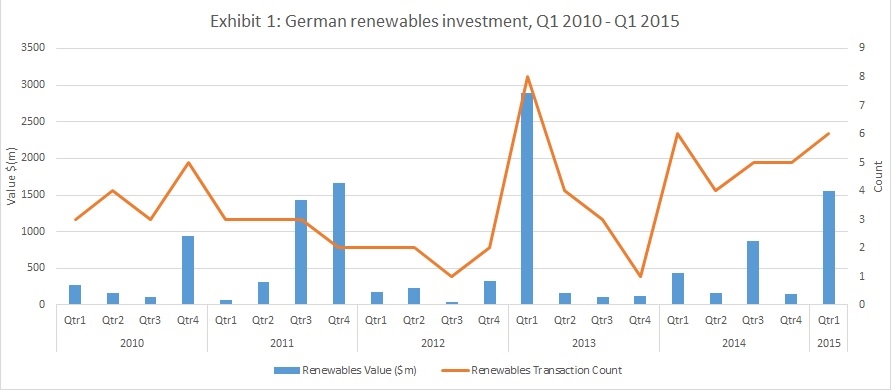

German renewable energy investment appears to be ascending again. Since the start of 2014, the country’s renewables sectors have, cumulatively, enjoyed three of their best quarters ever (see Exhibit 1).

Germany closed $1.56 billion of renewables investment in Q1 2015, up from $441.2 million in the same quarter of 2014, according to IJGlobal data.

Yet as renewables investment increases, gas-fired finance has collapsed. No gas-fired deals closed in the first quarter of 2014 or the first quarter of 2015. And major utilities are abandoning existing gas plants.

An E.ON-led consortium plans to shut down 1.3GW of gas-fired generators in Germany next year, citing “impossible” economics amid rising renewables capacity and low domestic wholesale power prices.

The two projects in question came online in 2010 and 2011, but have yet to make their money back for their owners. In 2014 E.ON’s Irsching 4 and 5 failed to sell power into Germany’s merchant markets. Only when network operator TenneT experienced temporary fluctuations in power were the E.ON plants used that year.

Global forces

Only a few years ago, natural gas was seen as the preferred fuel to bridge the gap in Germany between conventional generation and a renewables-reliant future. But the landscape has been reset – and quickly.

Coal had been expected to be phased out as Germany shifted further towards cleaner fuel sources. But the advent of cheap US liquefied natural gas (LNG) and the tumble in oil prices globally have encouraged German utilities to continue relying on home-grown coal and lignite.

“The global markets skewed prices in a way we didn’t anticipate,” says Wolfram Distler, partner at DLA Piper in Frankfurt. “Domestic coal is now cheap, US LNG has pushed gas prices up.”

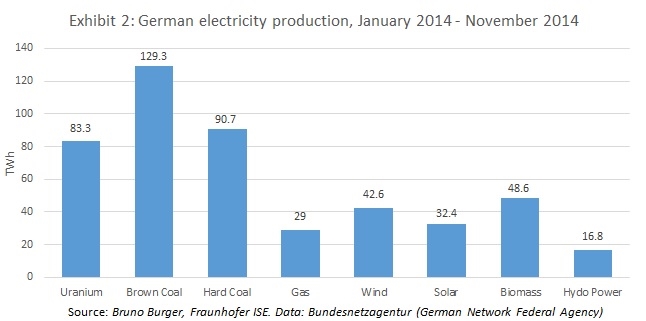

In 2014 30.8% of German net electricity production came from renewables, according to the Fraunhofer Society, a state-backed German research institute. But brown and hard coal, the institute reports, accounted for 45.8%.

Commodity prices account for much, but not all, of gas’ woes in Germany. German energy use is falling. Non-partisan industry statistics group AGEB found that energy consumption in Germany was down 4.7% in 2014 from the prior year. Meanwhile, renewables enjoy priority to the grid over gas.

The renewables rebound

Renewables regained political clout after Germany’s Renewable Energy Act came into force in 2014. This new state certainty is reflected in boosted investment over the past year after a disappointing late 2013 (see Exhibit 1).

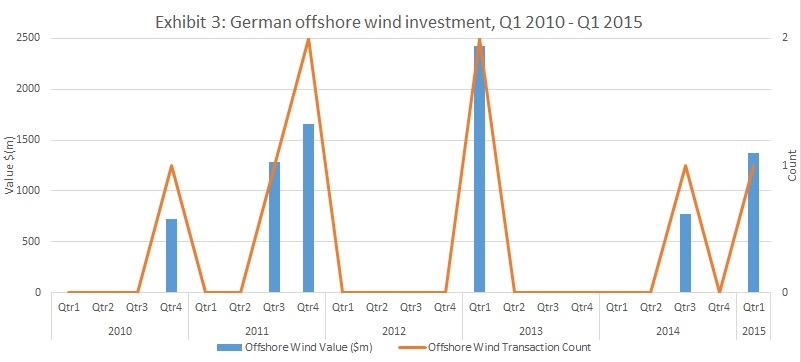

Offshore wind accounts for much of the growing renewables investment. Two mega offshore wind projects – Gemini and Nordsee One – closed on $4.3 billion in combined investment since the start of 2014. Only one quarter between the end of 2011 and 2014 had seen closed offshore wind investment (see Exhibit 3).

Distler suggests that offshore wind may provide steady medium-term generation – a cushion that gas projects were originally expected to supply. As gas projects have been idled, operating offshore parks have yielded steady, predictable power supplies, he says.

Future financings

EU - and self-imposed - demands for carbon reduction mean that new coal-fired or gas-fired projects are highly unlikely to close financing.

Existing baseload generators will still be called on, however, compromising short-term carbon reduction targets. This has been made clear by the government’s creation of a strategic reserve capacity, which will pay developers to keep conventional plants available in the event of a power deficiency.

But Klaus Bader, Norton Rose Fulbright partner in Munich, warns: “It is not intended to be a business model for conventional power. There may be another decade left for coal plant in Germany, but EU carbon reduction demands will be bearing down on this trend.”

Grid upgrades may provide flexibility that gas had been intended to provide, and which offshore wind is supplying in the short-term. Observers estimate that €30-40 billion will be needed to expand and modernise Germany’s transmission and distribution grids.

The tariff market for renewables will also change, as the German government rolls out a state-led tender system for new capacity instead. A test phase has been launched for solar development. “We may well see a rush for development in the next two to three years in renewables, as they try to take advantage of the last of the feed-in tariffs,” Bader says.

The future German energy mix, he adds, will rely on a strong basis of renewable energy sources, combined with the balancing mechanisms of the grid, exchanging power between north and south and also Europe-wide, and a limited national strategic reserve of conventional energy.

“Five years ago everybody thought gas plants would be the bridge technology,” Bader says. “But that sector has been the one suffering the most.”

Request a Demo

Interested in IJGlobal? Request a demo to discuss a trial with a member of our team. Talk to the team to explore the value of our asset and transaction databases, our market-leading news, league tables and much more.