US PPPs: Bridging the policy gaps

The State of Kentucky came close to joining a long list of US states that have enacted some form of PPP legislation as a means of delivering infrastructure, until its governor vetoed parts of the legislation a few days ago.

Kentucky’s state senate passed amendments to its House Bill 407 in March 2014, allowing the government to partner with private sector firms for greater use of PPPs in the state. However the amendments also involved banning tolls on the ongoing $3.5 billion Brent Spence Bridge project.

Whilst governor Steve Beshear is not exactly against PPPs, he is in opposition to parts of the bill that ban tolling on the bi-state, long-planned bridge project between Ohio and Kentucky. “It is imprudent to eliminate any potential means of financing construction of such a vital piece of infrastructure," he said in his veto statement.

The particular case of Kentucky may not be a fair reflection on whether US states are moving towards or retreating from the PPP model though, since Kentucky itself doesn't yet have a large pipeline to boast about. But the pressing need in the US for rebuilding ageing infrastructure, coupled with restricted public finances, has, in the last few years, led various states to move towards the PPP model.

Standardisation challenge

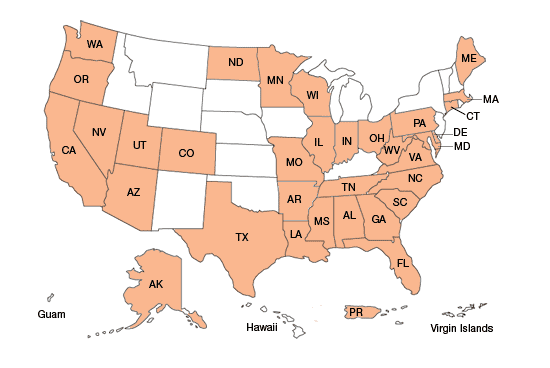

Today there are about 33 US states and one US territory (Puerto Rico) that have enacted statutes to enable the use of various P3 methods to develop infrastructure, according to the US Department of Transportation [see map]. The number is up from about 23 states back in 2006, reflecting both the growing need and acceptability of the model across the country. One of the most significant recent moves towards P3 legislation was in Pennsylvania in 2012.

(Source: US DOT)

While similarities in project procurement across states are far greater than the differences, it is still too soon to suggest that there is wide PPP standardisation. Cherian George, managing director - Americas, global infrastructure & project finance at Fitch says that the US is better at PPPs today than it was five years ago. “The trend on the legislative side is positive." He said, "Everybody is considering some form, but a national level model will always be hard for a country as large and diverse as US, there will never be one national standard.”

States like Virginia, Florida, Texas and Indiana have spearheaded enactment and application of PPP legislations across their constituencies. In fact Virginia’s Office of Transportation Public-Private Partnerships and Indiana's Finance Authority are state-led agencies which have been dedicated to innovation in procurement and financing.

Florida passed legislation in May 2013 allowing the state's existing P3 statute to spread across other sectors beyond transportation. The City of Miami has since proposed procuring various water treatment, waste and bio-solids projects using the PPP model, reflecting the wider application.

Since 2012 Pennsylvania, Connecticut, North Dakota and Ohio have all passed some form of PPP legislation. The state of Oregon too, which has several statutes regulating P3s, is now planning its first social infrastructure PPP - a new $250 million county courthouse.

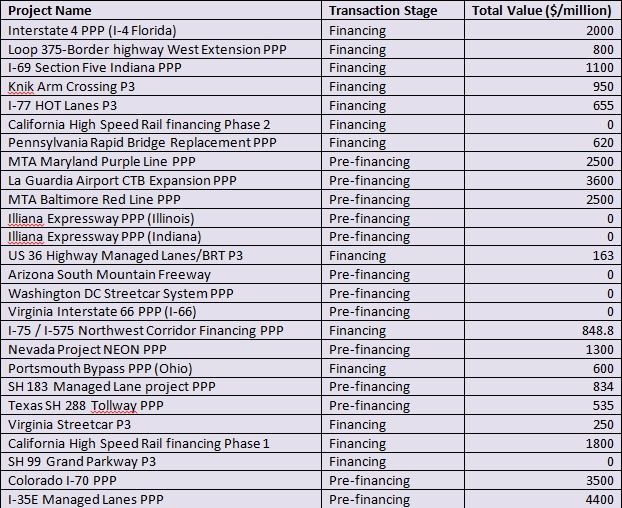

This is one of the first years since the model was introduced in the US when the country can boast of a steady, consistent and predictable PPP projects pipeline across various states [see table].

(Source: IJGlobal database)

George says the healthy deal pipeline is further affirmation that an increasing number of states have witnessed efficiencies after using the model, and are considering it for future projects. In addition he says it has also provided greater transparency from the public stand point.

That said there is still no consensus on whether PPPs are the ideal solution for procuring all types of infrastructure. The Alaska State Senate passed House Bill 23 pushing for a publicly financed solution for the Knik Arm Crossing Bridge, while California is toying with the idea of publicly financing its bundled highway project - the ARTI project - instead of the initially planned PPP method. In these instances, states may not have been convinced by the "value proposition" of using a PPP to deliver the project according to Geoffrey Yarema, Partner at Nossaman. "But this doesn’t mean the trend for PPPs has reversed altogether."

“Everybody is never going to be on the same page. Procurement methods and solutions will need to be worked out on a state by state basis," he adds.

Maturing sector

While PPPs are not a one-fit solution for all and standardisation is still some way away, what is evident is that the structures of the PPP model are gradually maturing and evolving in the US. For instance, availability payments - as a means of generating revenues instead of tolling - are becoming an increasingly common method for structuring the private sector compensation under PPP agreements for US transport projects.

The new move towards availability payment-based structures, although still subject to the annual appropriation risk, reduces overall risk for the private sector, according to Roderick Devlin, of counsel at Squire Sanders. Florida's I-4 managed lanes project, Nevada's Project Neon (I-15) and Pennsylvania's Rapid Bridge Replacement project will all be financed under availability payment based structures.

Innovation in project procurement is inevitable at a time when commercial banks and public authorities are feeling the liquidity squeeze.

According to figures by the American Society of Civil Engineers, the US needs to spend about $3.6 trillion on infrastructure by 2020 to recover from decades of neglect.

A lot of major US transport PPP projects are being financed via the government's low interest, attractively priced Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (TIFIA) loans and private activity bonds (PABs). But the US Highway Trust Fund which provides federal funding for transportation projects is likely to run into the red by September and MAP-21, which came into effect in July 2012 to fund surface transportation programs between 2013-2014, is set to expire at the end of that month unless extended.

Therefore in addition to applying greater standardisation in procurement models, such as PPP, the US will also need to continue to devise innovative ways to finance its infrastructure.

Request a Demo

Interested in IJGlobal? Request a demo to discuss a trial with a member of our team. Talk to the team to explore the value of our asset and transaction databases, our market-leading news, league tables and much more.