In the shadow of Colombia's 4G

Two weeks ago Colombia's President Juan Manuel Santos committed to partially funding the decades-long dream of a first metro line for Colombia's capital city. The decision was indeed welcome, as Bogotá suffers from high congestion levels and the average travel time to work for those in lower income areas is around two hours.

Colombia’s infrastructure procurement is best known for the country’s Ps47 billion ($24 billion) 4G road programme, but on the ground in Bogotá it seems the metro project is firmly on the investors' radar.

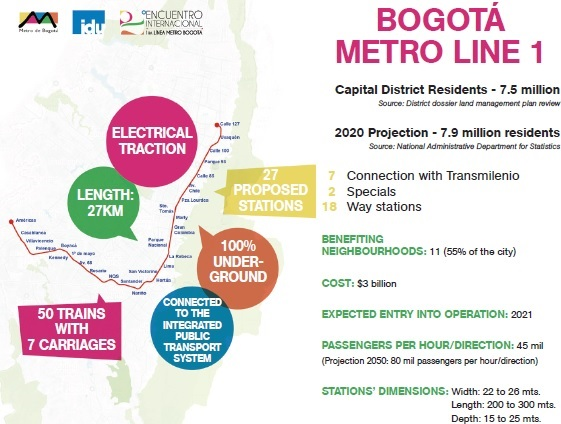

The Colombian government has pledged to fund 70% of the line’s $3 billion estimated cost. The city government would lean on multilateral, local and international banks to help fund the balance.

Decades in the making

The city needs a metro. Bogotá is the most densely populated city in the country and accounts for nearly a quarter of Colombia’s gross domestic product, yet its principal mode of public transit is the Transmilenio bus rapid transit system. The success of Transmilenio has led to higher urban traffic and prompted restrictions on the use of private vehicles. Metro de Bogotá would be the first underground metro line in Colombia. Only one of its cities, Medellín, has a light-rail transit system.

Bogotá has avoided overwhelming developers. “At least this time they have started with the one project,” says a Bogotá-based banker. “Usually, when you test any system you begin with one project.” While the system’s second and third metro lines are already under discussion, Colombia and Bogotá seem to be content to concentrate on developing just the first line.

The metro’s proposed timeline, though, is tight. Government officials expect feasibility studies, which have cost $35 million, to be completed in September. The National Planning Department of Colombia (CONPES) would then consider the project, and the bidding process could begin early next year. This timeline may prove ambitious. The government has yet to clarify which contracts it plans to award for the line, and whether it would use a concession contract to manage and operate the line, not to mention the fact that presidential elections are imminent and the outcome of which could significantly stall progress of the project.

No consensus has arisen among Latin American countries for metro projects. The Quito line in Ecuador was a purely public endeavour, while São Paulo’s fourth line features a hybrid model. For Metro de Bogotá, developers are thought to favour a concession, but banks say they are comfortable with either model.

Foreign developers and investors Alstom, AVB, Cobra, Daewoo, Mitsubishi and Siemens, are interested in the project, according to the Instituto de Desarrollo Urbano (IDU). Several have already visited Colombia to pitch their engineering expertise.

Local, international and multilateral banks are also studying Metro de Bogotá’s first line. They include the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB), Corporacion Andina de Fomento (CAF), the International Finance Corporation (IFC), BCIE, BBVA and Scotiabank. CAF and the IFC recently became shareholders in recently-established Colombian development bank Financiera de Desarrollo Nacional (FDN).

“If the government really makes the Bogotá metro availability-based or similar to the Lima metro, with government obligations and no traffic risk, a lot of investors will be very interested in participating,” says David Gonzalez, head of Latin American infrastructure at SMBC in New York. “Roads are needed, yes, but the metro is essential.”

The success of the metro, though, will depend on how Colombia’s project finance market copes with the strain of 4G. Banks may be keen to support the first metro line, but they may have little lending capacity left for infrastructure after all the 4G projects have reached financial close, possibly within five years.

4G Scepticism

The Colombian government has launched the first 4G concessions drawing unprecedented outside scrutiny/interest – and criticism from investors.

Investors have questioned the stringency of the National Infrastructure Agency’s (ANI) procurement criteria – as many as 10 bidders have been shortlisted for individual projects. “It is easier to have these discussions with fewer groups,” said Luis Ignacio Gómez, director of infrastructure at Bancolombia, at a March conference in Bogotá.

Colombia’s unwillingness to index payments to concessionaires to the US dollar means that local currency debt, from local banks, will be the main source of financing for the programme. The scale of the roads programme means that those banks may not be liquid enough.

4G features 40 separate PPP projects, but is just one component of a planned national infrastructure overhaul aimed at preserving recent strong economic growth. The pipeline of projects spans ports, railways, waterways and airports. But the structure and financing for the 4G concessions will almost certainly shape how Colombia procures later infrastructure projects.

Early signs are encouraging. Itaú BBA of Brazil, after its merger with CorpBanca, has quickly moved to establish a presence in Colombia. In October 2013, it fully underwrote $370 million in debt for Pacific Infrastructure’s Puerto Bahia, a new port located in Cartagena Bay on Colombia’s northern Caribbean coast. Itaú will also finance the forthcoming Olecar pipeline project.

“Capital levels in Colombia are tremendous compared to the 1990s. Local banks have a very important role to play in infrastructure projects, and international banks need to be made to feel comfortable,” said Juan José Montoya, BBVA’s head of project finance in Colombia. “The international banking segment is getting more and more involved and learning what a well-structured project is and what is not.”

The banks may find out soon. The first 4G concessions will be awarded as soon as May.

Request a Demo

Interested in IJGlobal? Request a demo to discuss a trial with a member of our team. Talk to the team to explore the value of our asset and transaction databases, our market-leading news, league tables and much more.