News+: Mexico on cusp of a black gold rush?

Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto is not one to shy away from reform. In his first year of office, he has proposed to reform most aspects of Mexico's society and economy, but his energy reform is considered to be his greatest test.

Peña is preparing to push a constitutional energy reform through Congress which threatens to drag the sector kicking and screaming into the 21st century.

Unlike previous reforms which have done little to attract oil heavyweights with the sufficient expertise to unlock Mexico’s untapped potential, if passed, Peña’s initiative to open up the nation's reserves to the private sector (announced in August) looks set to radically transform both its oil and gas and power sectors, which could in time set Mexico quite apart from its Latin American counterparts.

Why reform? Despite estimates that the country harbours more than 45 billion barrels of oil and 500 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, the country is reliant upon imports and its crude oil production is in decline.

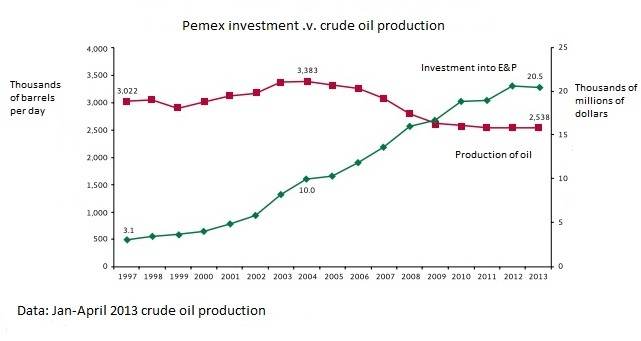

The average daily crude oil production dropped from a high of 3.4 million barrels per day in 2004 to 2.5 million barrels per day in 2013.

Source: Petróleos Mexicanos Institutional database June 2013

Petróleos Mexicanos’ (Pemex) monopoly over the country’s oil reserves is considered a reason for the sector ailing. It has been criticised for being both corrupt and hampered by archaic bureaucracy.

Moreover, Pemex does not have the technology or resources to tap Mexico’s deepwater oil reserves or shale layers and has instead played only in relatively shallow waters, of which the wanning Cantarell field located off the coast of the Yucatan Peninsula in the Gulf of Mexico is most emblematic.

Indeed, in 2012 only three exploratory blocks were authorised for shale gas and six in deep-water.

Peña also seeks to address Mexico's inefficient and concentrated power market in the energy reform. Suffocated by the state controlled Federal Electricity Commision (CFE), the market suffers from high consumer prices and insufficient capacity.

What will Peña achieve through reform? An end to Mexico’s dependence upon imports, improved power capacity and lower energy prices, hopefully.

In numbers, it will boost hydrocarbon production, namely crude oil production from 2.5 million daily barrels to three million in 2018, and 3.5 million in 2025 and natural gas production from 5.7 billion cubic feet to eight billion in 2018, and 10.4 billion in 2025.

The new contracts will redevelop shallow water fields or land fields, but the main target for foreign investment is developing deep water oil and shale gas plays.

Profit versus production

Mexico has a strong sense of patrimony towards its national oil reserves, which legally belong to the nation and its people according to Article 27. This dates back to 1938 when the oil and gas sector was nationalised by President Lázaro Cárdenas.

Consequently Peña has had to tread lightly with his proposed reform.

While the president has looked to how its Latin American neighbours have opened up their oil patches to private investment in order to drive production levels, he has opted for a profit sharing model over a production sharing model, a contentious and hotly debated move.

The fact that companies will not own the commodities they produce is thoroughly unpopular. But with their eyes on the prize is Mexico's unlocked potential too much to resist? Mexican government officials say so.

However, in light of the relatively few hand raisers for Brazil’s first pre-salt auction, it would be risky to simply assume participation from major players. Particularly as the auction for Libra was offered under a shared production agreement.

Will it go through? The general consensus is that yes, and sooner rather than later, despite strong opposition from the left, both moderate and radical, and grumbles from the right that it does not go far enough.

Dwight Dyer, Mexico-based political and security risks analyst at consultancy Control Risks, believes it will be passed as early as November.

The constitutional reform, which will require the support of the National Action Party (PAN), will be the first step in place to effectively green lighting private sector investment, with the second being regulatory reform. It needs a two-thirds supermajority in Chambers of Congress, and 50 per cent plus one of the state assemblies.

Regulatory reform only needs simple majority in Congress, which Peña's Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) can likely muster with help of minor parties, but which will very likely also include support from the PAN.

Opinions on the long-term outcomes of the reform are mixed. Some believe tangible contracts remain a while off.

Dyer said, “If the government’s plans go to schedule, we are unlikely to see the first profit sharing contracts discussed before late 2014/early 2015, providing by then the government has been able to sort out regulatory aspects”.

“In this respect it will be between eight and 10 years before major projects will come online, or before the deep-water wells begin to flow.”

Indeed, reform will not necessarily mean the big fish jump in first, Dyer commented “The reform could begin by attracting smaller and medium sized companies for whom the initial, expected gains will not be as large, but it will aim to attract the major IOCs for the riskier projects in deep sea waters”.

“The challenge now for the Peña Nieto government officials will be to figure out a way to have flexible contracts, more so than somewhere like Indonesia, in order to carry out deep sea and shale gas exploration and production”.

Black gold rush?

However, there is plenty of optimism regarding the reform, not only from Peña's government.

An advisor active in the Mexican energy space told IJ News "the energy and fiscal reform legislation proposed to Congress, particularly amendments to Articles 27 and 28 of the Constitution which go hand in hand with tax code reform, could be far reaching".

"Depending on the outcome, it could turn into a gold rush". They added that Mexico could subsequently steal the limelight from other Latin American countries seeking foreign investment, by drawing players which otherwise may have invested in countries such as Brazil, Colombia and Peru.

Request a Demo

Interested in IJGlobal? Request a demo to discuss a trial with a member of our team. Talk to the team to explore the value of our asset and transaction databases, our market-leading news, league tables and much more.