Narrowing opportunities for big PF banks

(Originally published in the Summer 2018 edition of IJGlobal)

For a number of years, the Netherlands has been the poster child for Europe’s PPP sector. The government counterparty is reliable, PPP revenues are predictable, and projects have been procured by a professional procurement agency, delivered under a bankable PPP model, and swiftly pushed through the various stages of procurement to financial close. Additionally, a number of Dutch projects have been sufficiently large to attract the attention of international lenders keen to exercise their balance sheets.

With activity in the Netherlands ramping up just as PFI activity in the UK – where the PPP model came of age – slowed down under the pressures of public and political opposition, the Dutch became an increasingly important market for infrastructure investors.

Within a short time, the Dutch market became the model for how PPP projects should be procured. Which is why changing dynamics in the Netherlands are important – it is likely they will be replicated across Europe.

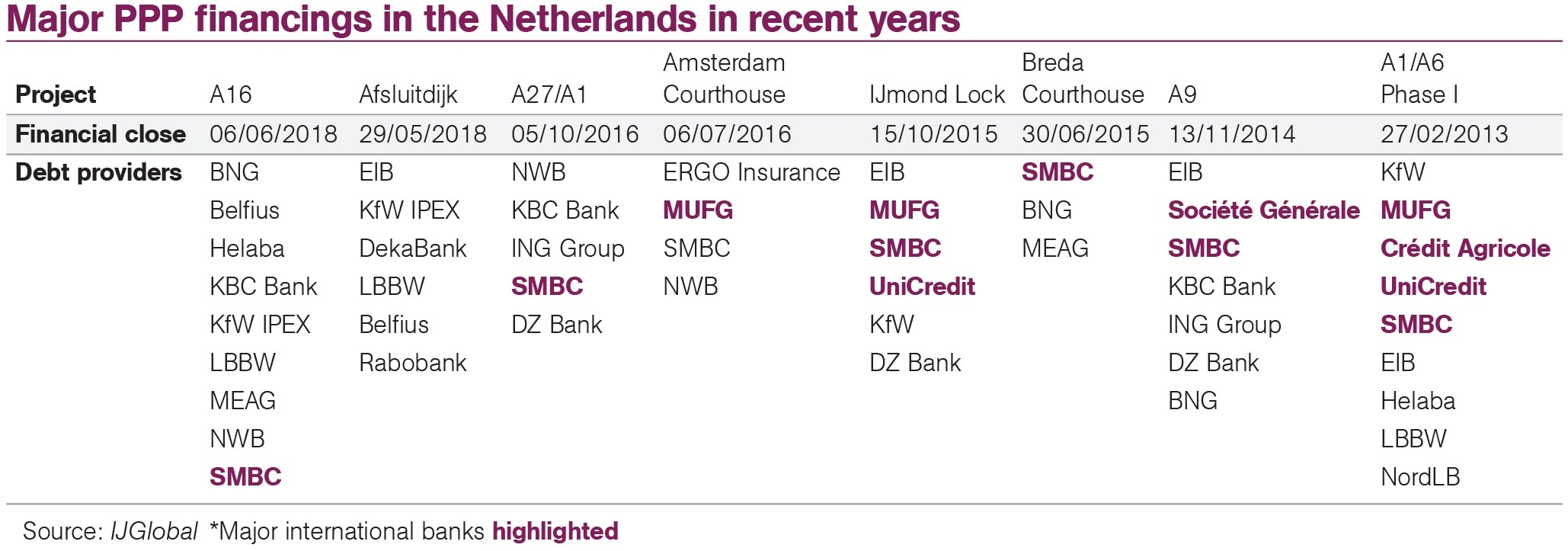

Projects closed over recent years in the Netherlands include:

- A16 road PPP

- Afsluitdijk dyke

- A27/A1 motorway PPP

- A6 road

- two Eefde locks

- Limmel lock

- Ijmuiden lock

- Princess Beatrix sea lock

In terms of financing, a number of smaller banks – including many Dutch and Belgian lenders, along with a handful of German landesbanks – have always been on the Dutch PPPs.

However, since before the 2008-2009 financial crisis – and, importantly, in the years that followed it – a number of big, international banks have also provided financing for Dutch PPPs. This group includes Japan’s SMBC and MUFG Bank, Italy’s UniCredit, the UK’s RBS, and Société Générale, BNP Paribas and Crédit Agricole of France.

The French banks typically provided shorter-term debt, and have for the most part not figured significantly on the more recent projects. Meanwhile the UK’s RBS, which required a state rescue during the financial crisis, has also long disappeared from this market. However, some of the other big, international lenders – including MUFG Bank, SMBC, and UniCredit – had until recently been more or less regular fixtures on these deals.

Which is why the absence of all the large, international lenders from the recently closed Afsluitdijk dyke project was particularly notable. And on the A16 road project that followed it, only SMBC was present, a pattern that is expected to be repeated for the soon-to-close Blankenburg tunnel.

As a result, the recent closed deals reveal a refocusing of financing back towards the local lenders, but also – at the same time – to institutional debt investors.

A BAM-led consortium reached financial close on the Afsluitdijk PPP project on 29 May (2018). The multilateral EIB was joined in financing the project by Belfius Bank of Belgium, local lender Rabobank, and German lenders DekaBank, KfW IPEX and Landesbank Baden-Württemberg.

A month later the Green Bow consortium – comprising Besix, Dura Vermeer, Van Oord, John Laing, RebelValley and TBI – closed on the €1 billion ($1.2 billion) A16 road PPP.

Much of the debt for this scheme was fronted by a group of smaller commercial banks from Belgium, the Netherlands, and Germany. However, they were joined by Japan’s SMBC and institutional investor MEAG.

MEAG has appeared on another transport project in the Netherlands – the Blankenburg tunnel, which was nearing financial close as IJGlobal went to press. Belgium’s KBC Bank and Germany’s KfW IPEX, both of which also lent on A16, are also on this deal, while Natixis has managed to muscle in alongside SMBC. But those big banks are again outnumbered in the lending group, with two development banks present and Samsung Life another institutional participating. And institutional investor participation on these deals is bigger than it seems – debt from these organisations was behind the contributions of some of the banks.

What’s behind the shift?

For one, many European banks have benefited from the European Central Bank’s quantitative easing programme, which has kept the banking sector awash with liquidity.

This impacts the comparative lending capability of Japanese banks such as MUFG Bank, possibly the most notable absence from the recent deals.

However, it must be noted that MUFG Bank did back two unsuccessful bidders on the Afsluitdijk project and one on the Blankenburg tunnel.

And the bank’s direct competitor SMBC was on the A16 and is expected to be lending to the Blankenburg tunnel, although that debt is likely to have ended up on the balance sheets of their institutional investor partners.

So it is the activity of these institutionals which is having perhaps the biggest impact.

With pricing margins falling close to 100bp over Euribor and tenors stretching far out into the 25-plus-year timeframe, it is getting harder for lenders to compete without tapping the institutional market. Because although quantitative easing has been providing banks with extra liquidity, Basel III and so-called Basel IV banking regulations are penalising banks for longer-term lending.

As a result, the larger banks often find these deals too costly and time consuming to be worthwhile – especially if they are simply going to pass them on to pension funds and insurers.

“The Dutch market is one the most sophisticated PPP markets in Europe, and one where institutional investors have been acting independently of banks for some time, which means that for us there really isn’t an angle to bring in institutional investors,” said Darryl D’Souza, head of financial sponsors, structured finance, EMEA at MUFG Bank (pictured on the left).

However, for some of the smaller, regional banks, institutional debt provides opportunities to stretch tenors and shrink pricing margins beyond their own capacity while employing their sector knowledge and structuring expertise.

Other sectors

“Project finance and PPP are still very core to our business, but we are being more selective. In the Dutch market, for example, we are just not able to compete with the local banks. So we’re not going to have a race to the bottom in terms of margins,” D’Souza said.

Much of the focus for MUFG Bank currently is on renewables, energy from waste, rail, housing finance, digital infrastructure – including telecoms towers, broadband and datacentres – leveraging off the bank’s advisory business, infrastructure M&A, and debt capital markets, he explained.

“And Europe is still very core, and we remain very active in the Middle East, but we are now also considering Africa on a very selective basis.”

Various lenders have also pointed to so-called core-plus and core-plus-plus deals, which are stretching the definition of infrastructure – as key areas of interest.

And for many banks it is easier to lend to renewables projects – where tenors under 20 years match project lifecycles – than to PPPs, where concessions are typically closer to 30 years, another source said.

Meanwhile, the banks’ advisory work has seen its importance grow as constraints have weighed on lending activity.

Ultimately, it all signals underlying caution about where the PPP market is going. “With margins still coming down, is this an asset class I want to invest in?” asked another banking source. Many are now more interested in regulated utilities, airports, and renewables, he said.

Capital reserve (and other) constraints

With the full impact of Basel III and Basel IV on capital allocation still not completely clear, this is clearly also impacting lending decisions.

One source even refused to discuss the topic, as coverage from IJGlobal will add to the stream of market chatter acting as a “self-fulfilling prophesy” to stem debt flows, he said.

Meanwhile, today’s borrowers’ market means sponsors are pushing banks as far as they will go – or not go, as the case might be – in terms of high gearing ratios and long tenors, and also in other areas. This includes security packages and cover ratios, all of which puts pressure on banks, making it harder for them to lend.

In any case, beyond acting as a conduit for institutional money, smaller banks are taking advantage of their competitive edge.

“The key advantage is that specialised banks are much more agile and flexible. Hierarchies are much flatter, we have no silo mentality and can turn around approvals pretty quickly,” noted John Philip Weiland, head of banking at Austria’s Kommunalkredit (pictured on the right), which has appeared on a number of deals over recent months.

While larger banks will typically only be interested in deals where they can take on larger debt tickets, this is not as much of an issue for the smaller players, Weiland added.

Which means some smaller players have been popping up in unexpected places.

Kommunalkredit recently hired a number of senior bankers from Deutsche Bank – including Bernd Fislage and John Philip Weiland – as part of its drive to boost its project financing expertise. The bank was a lender on the 2017 refinancing of the Tranvia de Zaragoza tram PPP in Spain, as well as for the A2 road PPP refinancing in Poland, with other deals on the cards.

“While we are a dedicated real asset player with a particular focus on infrastructure and energy deals at the moment, we are open in terms of how we finance the deals, whether its acquisition finance, or project finance. And we can do core plus, core plus-plus. That is much harder in larger institutions,” Weiland said.

Regional lenders in other markets

Regional lenders are crowding out competitors from further afield in an increasing number of European markets.

“In France this has happened a lot,” pointed out one source, arguing that local lenders often behave like cartels in their efforts to protect their home markets from foreign lenders.

And Norway seems to be going the same way, with the Rv3/Rv25 – the first road in the country’s current road PPP programme – brought to financial close by Skanska in late May (2018) with debt largely provided by SEB.

However, this was admittedly a relatively small project, costing around NKr2.6 billion ($316 million). So the upcoming NKr8.9 billion Rv555 project with its much greater complexity (think multiple bridges across numerous waterways in a densely populated area) may be a better bellwether for financing trends.

Local banks that are able to lend in local currency without taking on costs associated with currency swaps obviously have an advantage in Norway. But the Strabag-led consortium, which was unsuccessful in its bid for the Rv3/Rv25, did have around seven banks – mainly from Germany – backing its bid.

In any case, the Norwegian road projects reveal how the introduction of a new PPP model can also encourage greater dependence on local lenders.

Norway has limited experience of PPPs. In terms of roads, this includes only the E18 Grimstad-Kristiansand motorway, the E39 Lyngdal-Flekkefjord road, and the E39 Klett-Bardshaug road highway – all of which reached financial close between 2003 and 2006.

The model used for these schemes featured availability payments spread out across concession periods but no significant lump sum payment at construction completion. The deals faced criticisms over excessively high financing costs, particularly given the government’s deep pockets.

As a result, under a revamped Norwegian PPP model, a provision was introduced which states that half of a project’s construction costs will be paid by the government at completion.

However, this reduced dependence on long-term debt means the Norwegian road projects are less appealing to the wider European banking sector than they could have been otherwise.

Beyond the Rv555, there will be another project – E10/RV85 Tjeldsund–Gullesfjordbotn in Nordland and Troms County – which is guaranteed to be a PPP, and a number of other road projects that may yet turn out to be privately financed too, so it remains to be seen which banks will be involved in these deals.

Meanwhile, with what few pipelines existed in Europe now drying up altogether – observe Spain, which had provided hope to PPP hopefuls with a €5 billion road programme, which a new government has just shelved – it remains to be seen whether the Netherlands and Norway will set the tone for whatever greenfield deals do emerge across the continent. If they do, expect to see more deals financed on an increasingly local basis, as larger banks shift their focus away from project finance.

Request a Demo

Interested in IJGlobal? Request a demo to discuss a trial with a member of our team. Talk to the team to explore the value of our asset and transaction databases, our market-leading news, league tables and much more.