Renewables tenders in Turkey

It is not without its challenges, but the Turkish renewables market is providing ample opportunity for investment in greenfield projects.

Turkey needs to meet growing domestic power demand and increasing its renewable energy capacity forms an important part of the government’s strategy.

Some 10 years after the adoption of the Renewable Energy Law, Ankara introduced Renewable Energy Zones (YEKA) to allow for robust and structured investments in sustainable energy sources.

Several large tenders have been launched since, as the government tries to meet ambitious renewable energy targets.

Tenders streak

In late December 2017 Turkey awarded pre-licenses to 22 wind projects in nine regions with a total capacity of 2,130MW.

This tender followed another wind auction for 710MW in June 2017, which saw over 200 renewable energy firms competing for capacity.

According to transmission system reports, as of the end of November of last year (2017), the number of licensed wind power plants in Turkey had reached 161 – accounting for 7.8% of the country's total electricity generation. Turkey's installed wind capacity stood at 6.5GW.

According to IJGlobal data, capacity has grown even further since then.

The bulk (80%) of Turkey’s wind power plants are located in the Aegean and Marmara regions of the country.

Given the success of last year’s auctions, the government will include 1GW solar in its September offering and is due to launch its first offshore wind tender later this year (2018).

On the plus side

Turkey has become one of the fastest growing energy markets in the world – paralleling its economic growth over the last 15 years – which has also led to a more competitive domestic energy market.

The success of a privatisation programme – ongoing since 2002 – has resulted in power distribution now being completely held in private sector hands, while the privatization of all power generation assets is set to be completed within the next few years.

The aim is to increase installed capacity from 80GW today to 120GW by 2023. The Investment Support and Promotion Agency of Turkey estimates that the total investment requirement to meet this target is $110 billion, which is more than double the total invested over the last decade.

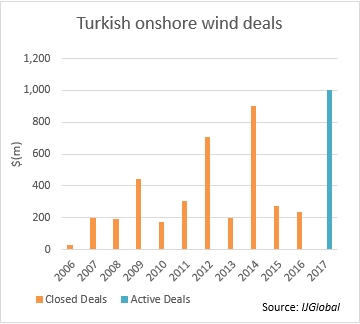

As IJGlobal data suggests, there is a considerable number of projects in the Turkish wind pipeline.

The government has put in place encouraging policies backed by favorable feed-in tariffs to increase the share of renewables – hydro, wind, solar, and geothermal – feeding into the national grid.

Growing the share of renewables to 30% by 2023 has been a staple priority in Ankara’s energy policy over the past few years. This will run in parallel to the government’s commitment to energy efficiency. It is enacting laws that set principles for saving energy – on both individual and corporate levels – as well as providing incentives for energy efficiency investments.

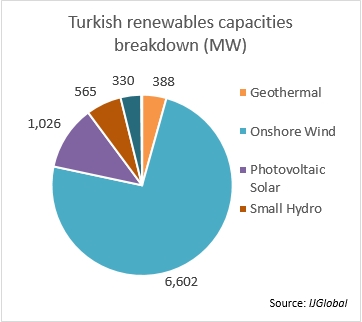

As demonstrated by IJGlobal data, the Turkish government has been on track with its targets to grow the share of renewables in its national energy portfolio.

Comprehensive measures have been set out with an intention to go big on new projects. The new YEKA model is particularly favourable for the commission of large-scale renewable energy projects through the utilisation of locally-manufactured components. Under the model, the largest-ever solar power auction in Turkey's history took place on 20 March 2017. A similar tender for 1GW wind power plants took place in August 2017, with local manufacturing and R&D requirements.

Cause for concern?

This focus on local content and local ownership is a potential challenge for international investors, however.

Turkish law sets out limitations when it comes to direct and indirect changes in shareholding – in both the pre-licensing and licensing periods of a renewables project. This generally rules out projects and portfolios changing hands – as is typical of mature European wind and solar markets, such as Italy and Spain.

Investors have expressed concern at frequent regulatory changes that occur with short implementation time frames, and insufficient evaluation of the wider consequences for the sectors concerned.

Some have also expressed concern over rule of law, including independence and impartiality of state institutions.

Moody’s this week (March 2018) downgraded Turkey’s sovereign rating to Ba2, following a previous downgrade in 2016 which pushed it into junk status. The credit ratings agency cited a continued weakness in its political and economic institutions.

But this does not appear to have significantly limited interest in renewables.

International companies have been keen competitors in the recent wind tenders. Germany’s Siemens, together with local majors Kalyon and Turkerler, won 1GW capacity, ahead of China’s Ming Yang, Denmark’s Vestas, and German rival Enercon.

Request a Demo

Interested in IJGlobal? Request a demo to discuss a trial with a member of our team. Talk to the team to explore the value of our asset and transaction databases, our market-leading news, league tables and much more.