Australia’s National Energy Guarantee

Earlier this month the Australian government proposed an energy policy change, the so-called National Energy Guarantee, which peaked interest around the globe. It is an attempt to address a growing problem for electricity grids everywhere: how to promote renewable energy generation while ensuring reliability of supply.

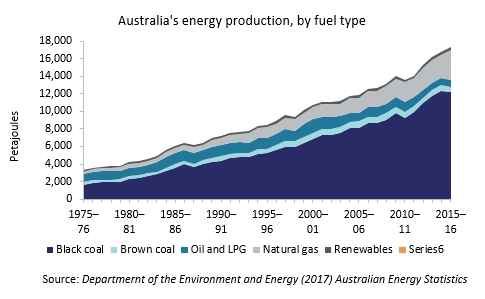

While government-set emissions reduction targets are predicated on significantly building out renewable energy capacity, these technologies are in nature intermittent producers of power.

And so the Australian government has come up with an emissions guarantee and a reliability guarantee, which will see direct regulation of electricity retailers and large energy users.

Retailers will have to have a mix in their portfolio: generation from dispatchable sources ready to fire up at speed, and from low-emissions sources, to meet their regulatory obligations. Under the proposed rules, non-compliance with the obligations would result in financial penalties, and eventually deregistration of the retailer.

There is a lack of detail on how exactly these new regulations will work, however. All market observers have to go on is an eight-page letter from the Energy Security Board.

Some targets are bigger than others

One potential stumbling block for the legislation is Australia’s political system. There will need to be cooperation and agreement among states in order to make any legislation work. Western Australia and the Northern Territory aren’t in the national electricity market, so those two jurisdictions could end up being covered by a federal electricity emissions reduction target for electricity, but unable to participate in the market mechanisms to help deliver it.

Then you have the issue of the fragility of the Australian government. Last week the Liberal-led administration was thrown into crisis when the election of deputy prime minster Barnaby Joyce was ruled to be invalid by the High Court due to his dual-citizenship. This decision has wiped out the government's slender majority in the House of Representatives, and could ultimately lead to the downfall of the current government in a country which has seen five prime ministers in the past seven years. The policy is very much the brain-child of the current administration and probably wouldn't survive without it.

And that is because there has been a fair amount of negative responses to some of the predictions in the report. The Energy Security Board estimated in its advice to government that by 2030 renewables would provide between 28% and 36% of the power mix.

This seems to contradict the findings of the recent review undertaken by Australia’s chief scientist Alan Finkel, which stated that under business-as-usual conditions, renewable energy would have reached 35% of Australia’s energy mix by that date anyway. With these new policies and with the cost of developing renewable expected to continue to fall, it seems safe to say that those estimates are conservative.

This has led critics of the government to suggest that its plans are in fact designed to stifle potential investment in renewables. The opposition Labor party has said that if it comes to power it will drive towards a 50% target for green power, regardless of whatever legislation may be in place.

What difference does it make?

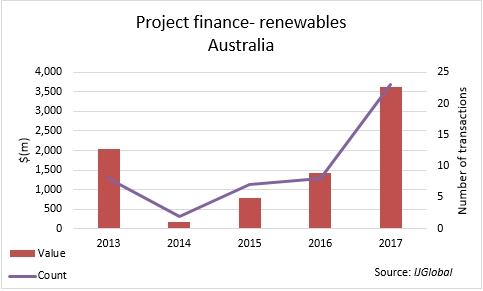

You could interpret the government’s estimate as misinformed, rather than malicious. Certainly the recent trend in Australia is for an acceleration of investment into renewable energy projects.

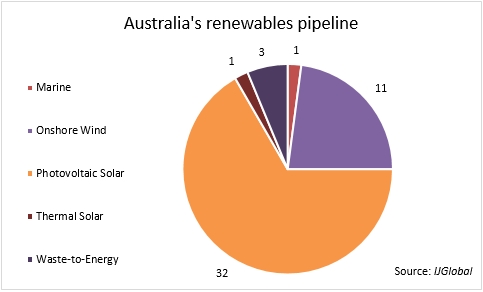

The total volume of project finance transactions in the sector has spiked massively this year, according to IJGlobal data. There are also a large number of pipeline projects in the market, most of which were launched in the last year.

Solar is by far the most popular technology for proposed projects, but large-scale wind will make a huge contribution in the future. Just this week, a developer looking to raise as much as A$8 billion to invest in offshore wind was granted permission to undertake a feasibility study by the state of Victoria.

So with or without the National Energy Guarantee, the Australian market looks set to continue growing. And given the legislative challenges it faces, and the precarious nature of the Australian government, we may never see what difference it could have made.

However, it will be interesting to track whether other countries decide that state intervention of this nature is worth pursuing.

Request a Demo

Interested in IJGlobal? Request a demo to discuss a trial with a member of our team. Talk to the team to explore the value of our asset and transaction databases, our market-leading news, league tables and much more.