How-long Bay?

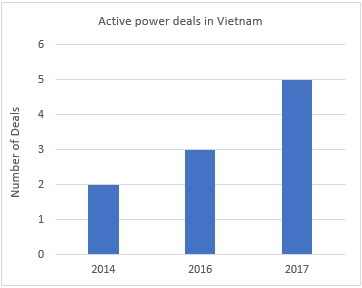

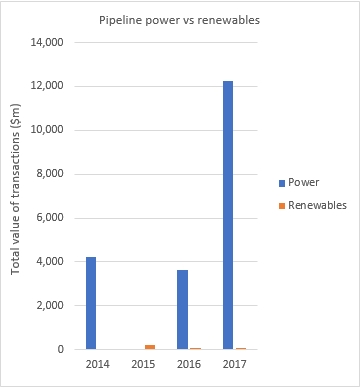

From a distance the Vietnamese power market looks in decent health. Five major coal-fired power projects, backed by established international developers, have received approvals from the government and, in theory, are moving towards financial close. These projects will collectively generate more than 6GW of power and cost a combined total of around to $12 billion to develop.

The country has also set a fairly punchy target of renewable energy contributing 10% of the country’s total power generation by 2030. Quite a feat if achieved, given renewables generation is minimal at present.

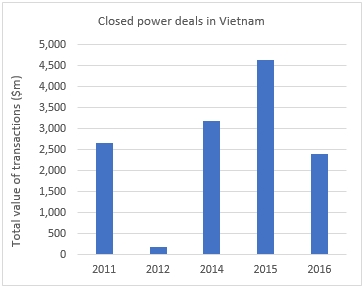

Peer a little closer however, and things do not looks so rosy. The total value of closed power financings in Vietnam has been declining in recent years (no power projects have closed yet in 2017) and those transactions that have closed have been in support of projects developed by local sponsors. The last IPP with a foreign sponsor to cross the financing finish line was AES Corporation and POSCO’s Mong Duong 2 back in 2011.

And of those five major coal-fired projects in the pipeline, some have been in the market for close to a decade. These delays to procurement are putting increasing pressure on Vietnam’s power networks. While the country’s GDP growth has been solidly above 5% for almost 20 years, electricity consumption levels are growing at around 11% a year.

The need for new generation is becoming more pressing and yet these major power projects are being delayed by a lack of clarity over state support and contract structures. The previous wave of IPPs benefitted from a comprehensive suite of government guarantees covering such things as state utility EVN’s credit risk and the convertibility of the Dong.

These backstops are no longer a given however. The government instead prefers to negotiate bilaterally with developers of specific projects, leading to discrepancies between them. For example, the sponsors of Nghi Son 2 are understood to have negotiated 100% currency convertibility for their project, while Nam Dinh 1 is being asked to settle for a guarantee to convert just 30% of revenues if local banks are unwilling or unable. This is a particular concern for international developers, given it is less than 10 years since the country's last liquidity crisis.

This uncertainty has parallels with neighbouring Indonesia, which has developed a bad reputation for painfully slow power plant procurement, exemplified by the 2,000MW Central Java coal-fired project which took five years to move from preferred bidder to financing close.

A power sector lawyer based in Vietnam told IJGlobal: “We are in the Central Java zone. We are not making Indonesia look slow.”

Little progress has been made on Vietnam’s renewables programme either, despite seemingly competitive feed-in tariff rates. The government published a draft PPA for solar projects in June which was largely seen as unbankable by the market. A revised version is due to be published in October.

How much the government addresses concerns over FX, termination payments, ‘curtailment’ exceptions to the take-or-pay structure and the use of local law for dispute resolution will be a guide to how quickly this market takes off.

Some wind and solar projects sponsored by EVN look set to move forward but substantial foreign investment will be needed to hit that renewable energy target. To enable that, the government is going to have to sharpen its pencil.

Request a Demo

Interested in IJGlobal? Request a demo to discuss a trial with a member of our team. Talk to the team to explore the value of our asset and transaction databases, our market-leading news, league tables and much more.