Back from the dead?

Spain wants to revive its renewable energy market, but concerns remain for investors, despite high levels of interest in a recent capacity auction.

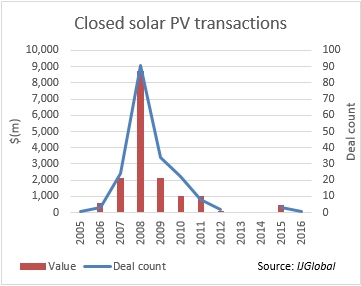

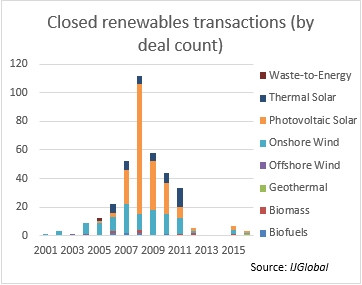

The Spanish government had granted generous subsidies to renewables producers since the mid-2000s, allocating $8.4 billion in subsidies for electricity production in 2012 alone, with 71% of this cash earmarked for renewables. These subsidies led to a massive investment in renewable power on a much wider scale than the government had expected. Spain ended up with a power surplus.

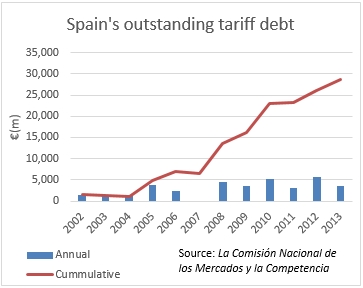

The authorities considered that the growth in regulated costs was so high that it could not be matched by the corresponding increase in fees paid by energy consumers. Consequently, tariff deficits substantially increased from 2008.

Debt accumulated from selling energy at regulated, below-cost rates. The amount of the outstanding tariff debt was estimated at some €30 billion (3% of GDP) by the end of 2013. Instead of passing this cost onto consumers, utilities were obliged to hold the debts on their balance sheets as state-backed debt.

Spain announced a moratorium on subsidies in 2012. According to the new regulations, all new renewable power plants in the country were not to receive any government subsidy on the energy they produce. Retroactive feed-in tariff cuts and other retroactive fees were also imposed and investors were forced to abandon projects. Some Spanish developers moved their focus to other jurisdictions in an attempt to spread the risk.

In 2013, 55,000 Spanish solar photovoltaic (PV) investors presented their legal claims at the European Court of Justice in Luxembourg over Spain's cuts to its solar feed-in tariffs.

As all these measures to contain the electricity tariff deficit had not been sufficient, in July 2013 the government replaced the feed-in-tariff system with a cap on earnings. The project companies for renewable power plants were now to earn a rate-of-return of around 7.5% (300bp over the interest on 10-year government bonds) over the lifetime of an asset. The law angered developers and investors who feared bankruptcy as projects failed to meet debt repayments.

The Spanish Photovoltaic Union (UNEF) estimated that 30% of PV projects would suffer cuts of around 40% of anticipated revenues.

The electricity tariff deficit reached €3.6 billion in 2013 in spite of the government's intention to have zero tariff deficit that year. This created uncertainty in the electricity system.

The subsequent three-year market standstill has put at risk the prospect of Spain meeting its EU commitments for 2020 - 20% of energy consumed in Spain to come from renewable sources - which is 4% higher than at present.

In October 2016 the government launched its first renewables auction since 2012, this time to procure 3GW. When awards were made in May 2017, wind projects scooped nearly half of all of the available capacity. The same month Spain announce it was to launch another auction for 3GW more of renewable energy.

With wind being the cheapest option for new power generation, its success as a technology in the recent auction could bring much-needed revenue stabilization to the market. This would help to restore confidence in the Spanish renewables market.

On the other hand, some think Spain’s plans are overly ambitious. The Association of Renewable Energy Producers (APPA) has stated its concerns that the intended accumulation of new power in two and half years demonstrates a lack of planning. Such an initiative could make the execution of projects more costly and even leave some of them unfinished.

Request a Demo

Interested in IJGlobal? Request a demo to discuss a trial with a member of our team. Talk to the team to explore the value of our asset and transaction databases, our market-leading news, league tables and much more.