Bigger blades, lower costs

Offshore wind appears to be a growing threat to other forms of energy production technologies in terms of cost per megawatt-hour, the figure often used in Europe to compare the price of technologies. So how are offshore wind developers trimming their costs?

As has been well documented, DONG Energy’s winning bid to construct the Borssele I and II plants at €72.70 per MWh upset the market in the summer of 2016 by halving the assumed cost of constructing offshore wind. Even lower tender wins followed.

Whatever the economics of these tariffs, one thing is sure: cheaper bids present developers with a problem. Returns compress as subsidies drop. And so value has to be squeezed out of the development chain elsewhere.

One trend within this drive for lower construction costs is a push to increase the size of offshore wind turbines. Bigger turbines are more efficient, cutting materials and installation costs and driving offshore wind closer to grid parity.

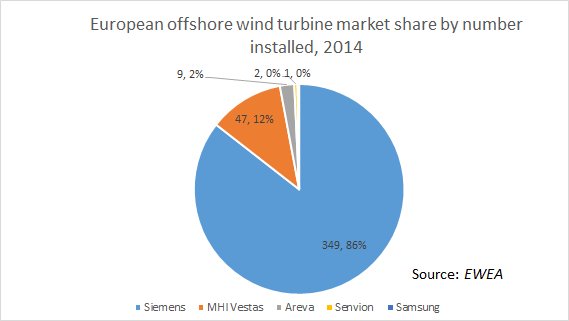

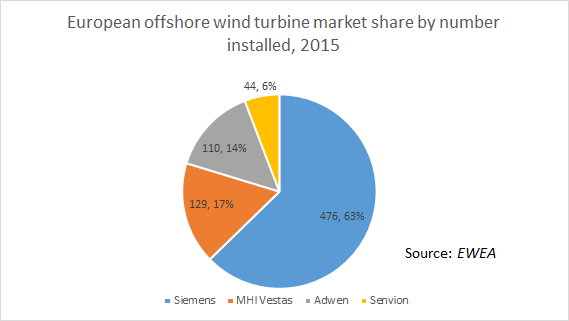

Those with successful products can, for now, enjoy a large market share. As IJGlobal data shows, the turbine market has been dominated by a handful of manufacturers in recent years: Siemens has taken the lion's share, with the second most active supplier MHI Vestas still some way behind.

Sales of 4-6MW turbines have dominated the market for the past five years. According to the European Wind Association, the latest available figures show the average offshore wind turbine size was 4.2MW in 2015, a 13% increase over 2014, when the average offshore wind turbine size was 3.7 MW.

And developers are still looking to scale up for new developments. Projects due to enter construction this spring, like the €1.2 billion, 370MW Norther offshore wind farm situated on the Belgian continental shelf, will use MHI Vestas’ V164 8MW turbines, as will the UK’s in-construction Burbo Bank Extension and Walney Extension projects.

The next goal for the industry is a commercial 10MW turbine, and Siemens, GE and MHI Vestas are all vying to create the market-leading blade at this size.

Increased demand means onshore and offshore wind has become a big earner for businesses previously reliant on conventional power. GE offshoot GE Renewable Energy said on 20 January 2017 that it booked renewables product orders totalling over $10 billion in 2016, up 38% on 2015.

One such order was for nacelles for the 396MW Merkur offshore wind farm in Germany, the production of which started at its St Nazaire facility in France in late 2016. GE has aims to become one of the top three players in the offshore wind industry globally.

One Dutch bank told IJGlobal last week there is talk of sponsors dragging their heels on orders until the next generation of 10MW turbines are released. One issue with a wait-and-see policy by developers is that there is no guarantee of when the next-generation turbines will become available. Despite the obvious demand, there has been talk of 10MW turbines coming to market for years and yet developers are still waiting.

Request a Demo

Interested in IJGlobal? Request a demo to discuss a trial with a member of our team. Talk to the team to explore the value of our asset and transaction databases, our market-leading news, league tables and much more.