Data analysis: EU broadband development

The European Union’s previous target for internet connectivity consisted of rolling out basic broadband across all regions of member states, a goal that was achieved in 2013. Since then, new targets have been set.

The European Commission's Digital Agenda is part of the Europe 2020 Strategy which sets growth targets encompassing a number of activities, industries and economic metrics to be achieved by 2020.

Within these objectives, the 28-member group now hopes to achieve download rates of 30 Mbps for all its citizens and at least 50% of households subscribing to internet connections above 100 Mbps by 2020.

In September this year, the Commission adopted a strategy called Connectivity for a European Gigabit Society. This strategy aims to address the availability and take-up of very-high-capacity networks and is expected to lead to the implementation of uninterrupted 5G coverage for all urban areas and major terrestrial transport paths, as well as access to connectivity offering at least 100 Mbps for all European households by 2025.

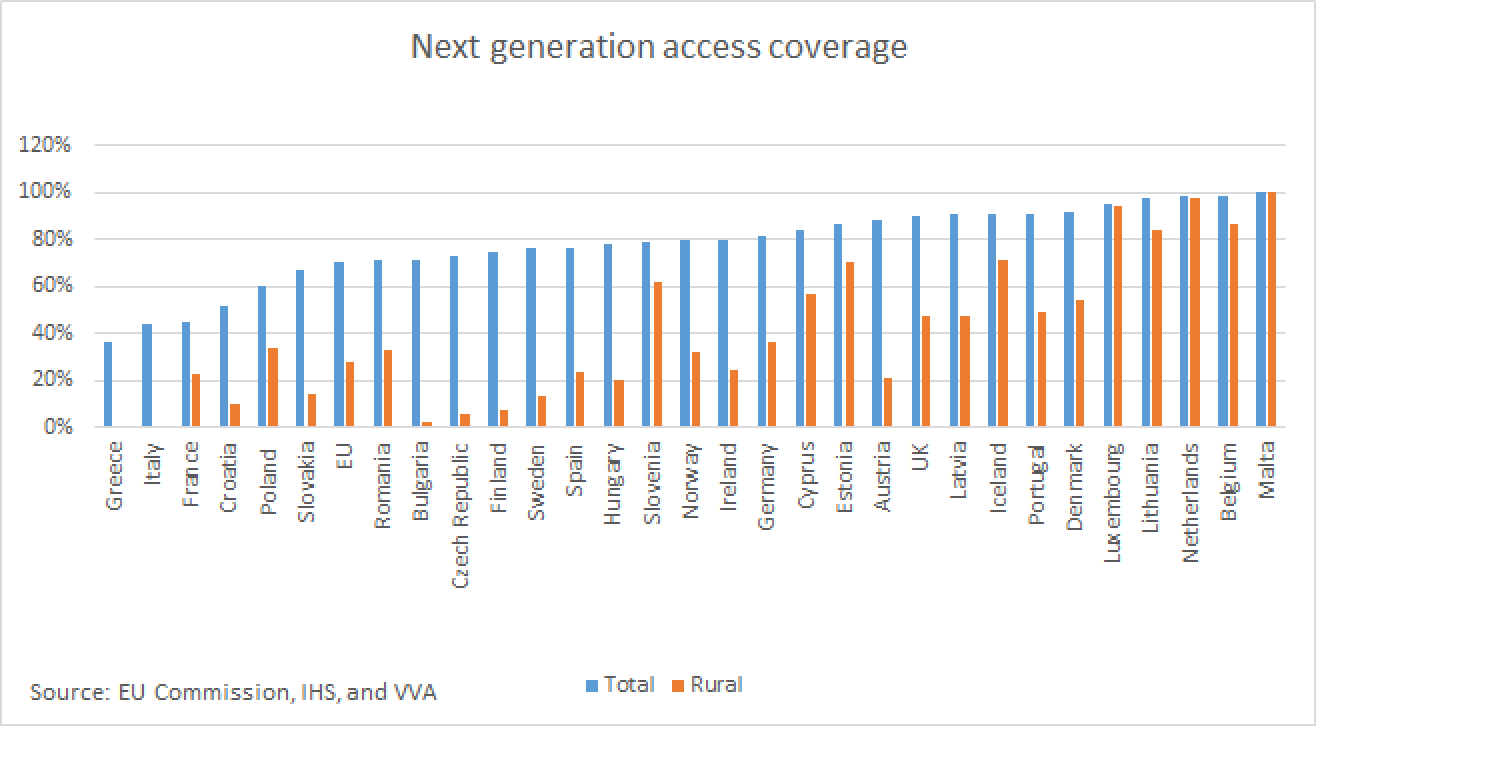

Existing standards of internet connectivity across the EU are disparate, with rural areas lagging quite behind their urban peers.

While basic broadband—including all technologies—is available across the EU, so-called next generation access (NGA), which includes VDSL, Cable Docsis 3.0 and FTTP capable of delivering at least 30 Mbps download is only available to 71% of the population.

Moreover coverage in rural areas is lower. While basic fixed technologies are accessible to 91% of the population in these regions, NGA is still only available to 28% of EU rural dwellers. Differences between countries are also large. While fixed broadband coverage is at levels above 86% in all countries, with many at almost 100%, NGA penetration varies.

In Italy, the most recent data provided by the EU reveals that rural NGA access is non-existent. Meanwhile, in Greece it reaches a mere 0.5% of the rural population, and Bulgaria’s rural availability of NGA is at a paltry 2.7%. At the same time, some countries, including Greece and Italy, are struggling to even roll out this technology in urban areas.

However, in other parts of the EU, rural and urban NGA connectivity is already at almost 100%.

As a result, plans to increase connectivity differ from country to country.

For some countries, objectives exceed EU targets. In Luxembourg, the national broadband plan is targeting networks with ultra-high-speed rates of 1 Gbps for 100% of the population by 2020. In France, where the country’s National Broadband Plan, France Tres Haut Debit was published by the government in 2013 and updated in 2015, the target is to achieve 100% coverage with 100 Mbps by 2022, thus surpassing the EU’s target, albeit with a longer time frame. Meanwhile, Germany plans to provide broadband connections with transmission rates of at least 50 Mbps for all households by 2018. However others, such as Bulgaria, are still tackling so-called white areas with no internet access.

The UK, where the government is aiming for 95% coverage with 24 Mbps by 2017, is favouring a technology-neutral approach that will encompass fixed, wireless and satellite projects. In contrast, France’s National Broadband Plan is focused on reaching its targets via fibre-to-the-home technology.

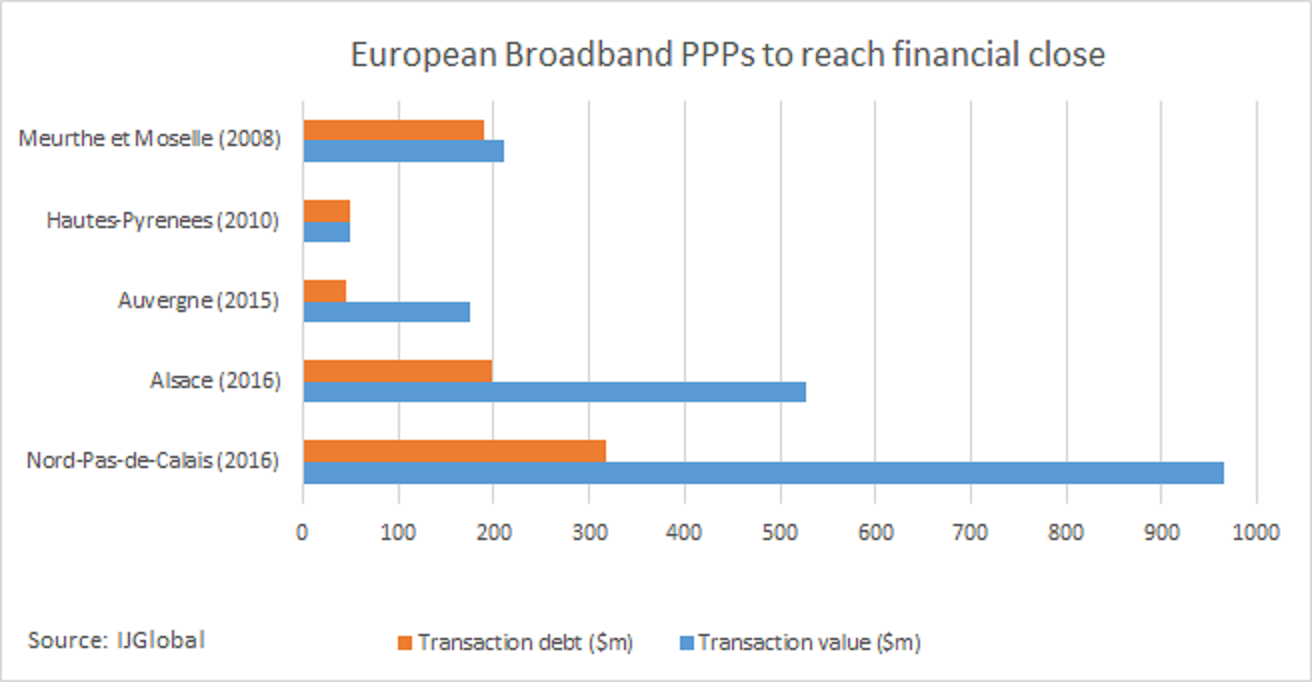

As IJGlobal data reveals, a number of broadband PPP deals have closed in France over recent years, with the latest transaction having closed in November 2016, achieving the largest transaction value and regional coverage.

Meanwhile, as reported by IJGlobal in January this year, Ireland’s Department of Communications, Energy and Natural Resources issued a contract notice for a 25-year concession to deliver, finance and operate a new NGA network for an area covering 750,000 premises. In July Eir, Enet and SIRO were shortlisted as bidders for this concession.

In terms of financing, some countries’ broadband programmes are primarily state-funded, while others are seeking private financing in a combination with state grants. And while it has been observed that in some cases initial projects struggled to obtain financing, the projects that followed often had an easier time.

*EU data from 2015, reflecting the most recent statistics available.

Request a Demo

Interested in IJGlobal? Request a demo to discuss a trial with a member of our team. Talk to the team to explore the value of our asset and transaction databases, our market-leading news, league tables and much more.