Data Analysis: Corporate PPAs

Companies sourcing their own power is not a new concept: large industrial factories, for example, have been drawing their energy from on-site power plants from decades.

In the past five years, however, there has been an increasing trend for businesses to enter into contracts with individual energy companies and projects to guarantee power supply.

Traditionally, utilities are the major offtakers of energy, signing power purchase agreements (PPAs) with developers, with power then sold into local and national grids. But sponsors now have a growing array of companies willing to become the exclusive offtaker for their projects under corporate PPAs.

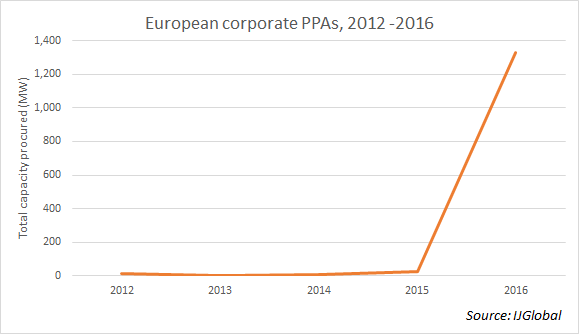

IJGlobal data shows major growth in European corporate PPA activity this year – from 27.8MW of capacity signed in 2015 to 1.32GW in 2016 to date. 2014 saw 6.1MW of capacity contracted, while 12.3MW was recorded by IJGlobal in 2012. All of the power procured in IJGlobal’s data is from renewable sources, primarily wind and solar.

It should be noted that the figures represent only publically disclosed capacity. Many more PPAs are likely to have been carried out in this time period on a private basis. MacDonald’s, for example, is known to have signed corporate PPA deals across Europe, but has not disclosed any information on them. But the surge seen in 2016 is the result of a confluence of factors, market participants told IJGlobal this week.

Renewables revolution

The smaller scale of renewables projects fits the power requirements of individual businesses, the vast majority of contracted projects being sub-100MW, compared to the gigawatt-scale conventional power PPAs utilities can handle.

Companies are also under increasing pressure, both politically since the COP21 summit last year and at the corporate level through the RE100 initiative, to reduce their carbon footprint, and sourcing power directly from renewables projects makes this easier.

For sponsors, falling returns for renewables have fed into the growing suitability of corporate PPAs. Subsidies have shrunk, and in some countries disappeared altogether, as technologies move towards grid parity. Across the EU, countries are being urged to switch to competitive auction systems for procuring renewables, as has already happened in the UK, Netherlands and Germany. In 2016, this is coupled with depressed electricity prices. All these factors have resulted in lower, and by no means guaranteed, returns for sponsors.

And so they have started to look for other ways to guarantee steady returns. For sponsors, a corporate PPA can offer a fixed rate of return for 10 or 15 years, insulating them from the fluctuations of the wholesale electricity market.

Who is buying?

Some of the world’s largest corporates, such as Google and Facebook, have made the most significant impact in the corporate PPA market. By virtue of their size, such major corporations tend to consume a lot of energy. With power prices remaining low throughout 2016, Baker & McKenzie’s Marc Fevre says that it’s a good time to sign a corporate PPA. "By locking into a low price for 15 years, corporates are effectively taking a hedge on long-term power prices."

He warns that banks are still adjusting to the trend when it comes to providing debt for projects backed with a corporate PPA. "Banks are used to financing projects backed by utilities," he says. "But they now have to take a view on the long-term credit worthiness of counterparties in different, more volatile sectors. Take a corporate PPA signed for a data centre, for example. Will data centres still be required in 15 years’ time? It’s a different sort of credit analysis."

DLA Piper’s head of renewable energy for EMEA, Natasha Luther-Jones, has worked on a number of corporate PPAs and co-authored the recent paper "2016: The Year of PPAs and the corporate green agenda" . She says banks will soon acclimatise to the presence of corporates as offtakers when looking at deals. “With a general move to a no incentive, auction-based regime in Europe, as a bank or investor, renewables projects are going to become less bankable and attractive. ” She argues the addition of a corporate on board improves this. “These corporations have strong balance sheets, often with investment grade ratings. They’re also willing to pay a premium for renewable energy, so the inclusion of a corporate PPA will often be a key component for new projects being bankable. ”

Looking ahead

Market observers expect the increasing use of corporate PPAs to continue. "The scale of corporate PPAs is relatively small at the moment," says Fevre, "but this trend is reflective of changes in the power sector as a result of increased renewables capacity in general. I think it will be at least as active in 2017 as this year."

Next year, consented-but-unfunded renewables projects may be strong candidates for corporate PPAs, Luther-Jones suggests. In Scotland, for example, there are a number of shovel-ready wind projects which failed to meet the deadline for the UK’s outgoing ROC accreditation. She predicts that mid-tier businesses will start engaging with developers, not just global giants. She also envisages developers clubbing together to offer larger capacities, and businesses in turn banding together to get better deals for their offtake power price. But, she says, that could add complexities. “What sort of credit support would you have to have in place if you aggregate mid-tier off-takers? What happens if one project fails?,” she asks.

In a post-COP21, post-subsidy world, the industry will have to find answers to these questions if sponsors are to maintain their margins and corporations are to keep their green promises.

Request a Demo

Interested in IJGlobal? Request a demo to discuss a trial with a member of our team. Talk to the team to explore the value of our asset and transaction databases, our market-leading news, league tables and much more.