Malaysian malaise

The 1MDB scandal is in the news again this week, with former Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad accusing neighbouring Singapore of not doing enough to stop alleged money-laundering by the investment fund. It is more than a year since the first allegations against 1MDB surfaced and since then the Malaysian government, and in particular current Prime Minister Najib Razak, have been dragged in to the imbroglio.

Deloitte recently stepped down as auditor to 1MDB, and both EY and KPMG previously parted company with the developer over disputes surrounding its accounts. 1MDB remains under investigation by authorities in several countries, including the US, Singapore and Switzerland.

It might be reasonable to assume that the scandal would have devoured a good deal of the government’s capacity over the last 12 months, and that consequently there would have been a slowdown in the procurement and completion of infrastructure transactions.

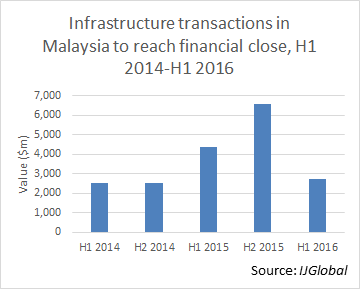

The total value of transactions reaching financial close during the first half of 2016 ($2.75 billion) has certainty declined significantly compared to H2 2015 ($6.58 billion), but was higher than the value of transactions closed in both halves of 2014.

However, there have only been two transactions to reach financial close in Malaysia since 1 January 2016, and one of these accounts for almost all of the total value of transactions. 1MDB completed the sale of its power unit Edra Global Energy to China General Nuclear Power Corporation for $2.3 billion in April. The sale was as a direct consequence of the scandal and the investment fund’s mounting debts. The only other 2016 deal was the $447 million Pertama Ferroalloys financing. The debt for this deal came exclusively from a mixture of Chinese and local commercial banks and development finance institutions.

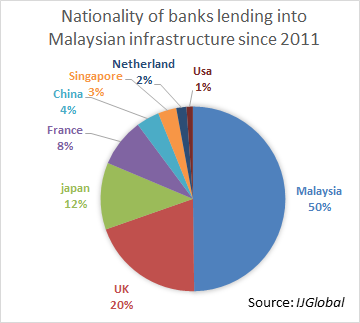

This growing dependence on Chinese capital is not typical for Malaysia. The country has a strong local bank market and since the start of 2011, half of all debt for its infrastructure projects has come from Malaysian banks. Chinese lenders have provided just 4% of total debt over that period.

There are still plenty of energy and infrastructure projects in the Malaysian pipeline, but the signs don’t look good for many of them reaching financial close soon.

Request a Demo

Interested in IJGlobal? Request a demo to discuss a trial with a member of our team. Talk to the team to explore the value of our asset and transaction databases, our market-leading news, league tables and much more.